|

Fortunes have been made in Texas, Arizona, California, Nevada, and New Mexico in agriculture, ranching, mining, gaming, recreation, energy, and development. For many decades, fast-growing, sun-washed cities in the region attracted people seeking a place to start anew and prosper. Cheap land and available resources lured entrepreneurs, retirees, recreationists, and businesses to this arid land. This frenzy of growth was lubricated by seemingly limitless supplies of fresh water pumped from relict groundwater or transported across the baked landscape by vast government projects. This cheap supply kept electrical generating facilities humming, maintained verdant lawns and golf courses, filled shimmering reservoirs, and slaked the thirst of lush fields of cotton, grain, fruits, and vegetables. Fortunes have been made in Texas, Arizona, California, Nevada, and New Mexico in agriculture, ranching, mining, gaming, recreation, energy, and development. For many decades, fast-growing, sun-washed cities in the region attracted people seeking a place to start anew and prosper. Cheap land and available resources lured entrepreneurs, retirees, recreationists, and businesses to this arid land. This frenzy of growth was lubricated by seemingly limitless supplies of fresh water pumped from relict groundwater or transported across the baked landscape by vast government projects. This cheap supply kept electrical generating facilities humming, maintained verdant lawns and golf courses, filled shimmering reservoirs, and slaked the thirst of lush fields of cotton, grain, fruits, and vegetables.

But now, with limited water supplies stretched thin by years of lingering, grinding drought, and growing demand from cities, the rural water users and agricultural customers are feeling the weight of municipal power and influence. Cities have more political clout than rural areas because they have more representatives in the state legislatures and more votes in the U.S. Congress. They also have more money, allowing them to spread their reach across great expanses in the quest for diversified water resources. There is a truism in the American West that “water flows uphill towards money.”

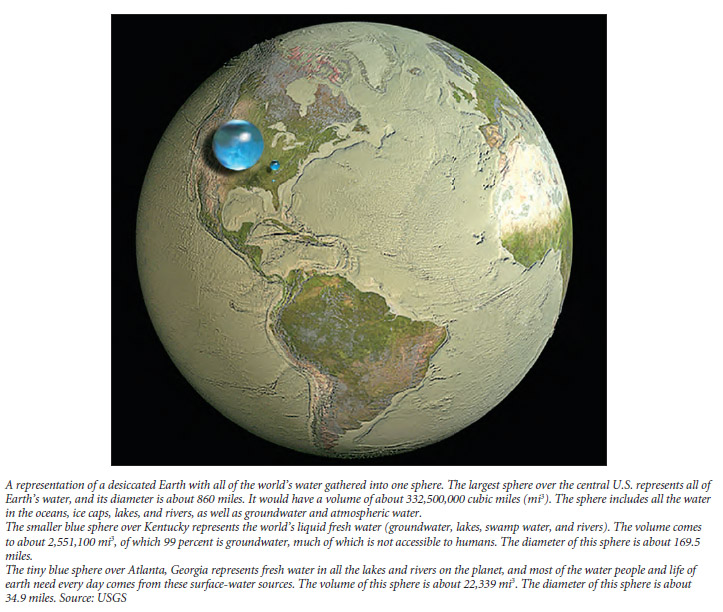

But what happens when the rain stops and the rivers drain into the sand? The ongoing drought presents a major risk to water resources across the parched landscape. Historically, water has been distributed through a complex series of local, state and regional water-sharing agreements and laws. Virtually every drop of water flowing in the American West is legally claimed or allocated, sometimes by several users, and the demand is increasing as populations grow. Christopher R. Schwalm, a research assistant professor of earth sciences at Northern Arizona University, stated in an August 2012 New York Times article titled, “Hundred-Year Forecast: Drought,” that many Western cities fundamentally have to change how they acquire and use water. Some regions will become impossible to farm because of lack of irrigation water and thermoelectric energy production will compete for limited water resources.

Colorado River

Water users in the American West have relied largely on the largess and engineering of the federal government to manage and move water. One of the earliest, and still the keystone, of these immense government water projects is Boulder Dam. Renamed Hoover Dam, it was constructed between 1931 and 1936 in Black Canyon just south of Las Vegas during the dark days of the Great Depression. Hoover Dam was designed to impound the Colorado River to create Lake Mead, manage the resources of the river, and generate electricity. “The Colorado River is the lifeblood the American Southwest,” said Jeff Weider in an Op-Ed piece published in April 2013 titled “Why Many American Rivers Are Running on Empty.” The river provides drinking water for over 36 million people across seven states, irrigates 15 percent of our nation’s agricultural output, and supports a $26 billion recreation economy.

In December 2012, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency charged with managing the Colorado River, released a report emphasizing that there is not enough water in the river to meet the current demand, let alone support future demand increases. The reported noted that more water leaves the Colorado River than enters it each year because of chronic drought, population growth, energy development, and climate change. In the last 13 years, water storage in the basin has decreased by 40 percent. A smaller pie means that someone will go hungry.

New Mexico New Mexico

In parched New Mexico, the Rio Grande has run dry. Some wags have dubbed the water course the “Rio Sand.” The dismal conditions of 2011 and 2012 resulted from the warmest and driest two-year period in New Mexico since forecasters began keeping records more than a century ago. In 2012, precipitation was just 60 percent of normal. The lingering multi-year drought in New Mexico has punished rural communities and the agricultural industry.

A dispute erupted at the 2014 meeting of the Tri-State Compact Commission in Santa Fe. The Compact, formed in 1939 by the governors of New Mexico, Colorado, and Texas, manages the resources of the Rio Grande. Representatives of Texas have asserted that New Mexico is withdrawing so much groundwater that the flows of the Rio Grande into Texas have been diminished, violating the terms of the Compact. Logan Hawkes reported in the Southwest Farm Press in March 2014 that the New Mexico Attorney General Gary King countered the claim and argued that groundwater was being pumped along the length of the river, including in Texas, and said that groundwater was not part of the Compact agreement. This conflict has moved to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“We are really facing some extraordinary challenges,” said Dennis McQuillan with the NM Drinking Water Bureau. He pointed to residential wells outside of Santa Fe that are going dry and the potential for the city of Clovis to drain its aquifer in the next 20-40 years. From the chile fields and pecan orchards of the Hatch and Mesilla valleys to Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and beyond, New Mexicans are facing tough choices and dire consequences reported Susan Montoya Bryan in an article titled, “NM grapples with tough choices,” published in Associated Press in March 2013. New Mexico is now a major producer of pecans, generating millions of dollars for the state’s economy. Unlike the unplanted fields of seasonal crops, the decades-old trees cannot go a year without water. Pecan trees, native to the southeastern United States, can tolerate the searing summer temperatures, but they must have some water to survive. Pecan growers rely mostly on wells to irrigate. But without a flowing river, the aquifers that feed the wells have little chance of being recharged. “When that river is flowing, everything is fine,” said Dickie Salopek, whose family has hundreds of acres of pecan trees in Dona Ana County, the top pecan-producing county in the U.S. “When it’s not flowing, you’d better be thinking outside the box.”

Texas

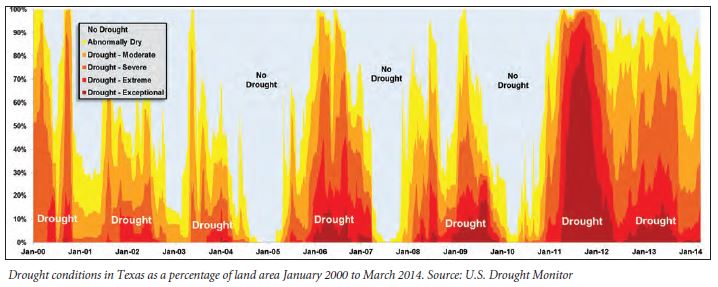

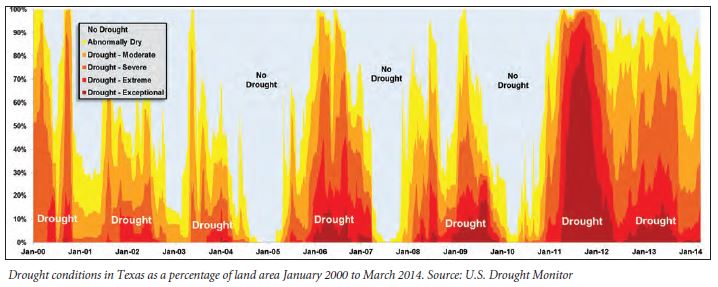

In 2011, Texas suffered through its worst one year drought in history. Wildfires raged across the state, millions of trees were lost, livestock herds were decimated, hay was trucked in from hundreds of miles away, river flows diminished to historic low levels, and reservoirs dropped to catastrophic levels under an unrelenting sun. The Governor, citing “dire conditions” across the state, “higher than normal temperatures,” and low rainfall issued an emergency disaster proclamation and designated April 22 - 24, 2011 as official days of prayer for rain. On January 23, 2013, the Governor issued a renewed drought disaster proclamation because “drought conditions have reached historic levels and continue to pose an imminent threat to public health, property and the economy.”

The mounting precipitation deficits across most of the state stress both water supplies and wildlife. “We’re going into the third year of drought,” Matthew Bochat, of the Bee Country Agricultural Extension in South Texas said recently, and some farmers are “just hanging on.” Two significant reservoirs, Buchanan and Travis, are only 38 percent full and water inflows are at a record low. And for the third consecutive year it is unlikely that any water will be released downstream. The Lower Colorado River Authority that oversees the reservoirs prioritizes its users. The highest priority users are the municipal clients and industrial customers such as power plants that need water to make electricity. Downstream rice farmers who need water for irrigation and the salty Gulf Coast bays that require freshwater inflows to maintain healthy ecosystems, are cut off during years of drought, as has happened since 2012.

In south Texas, the Rio Grande provided year-round irrigation water to generations of citrus and melon growers. But the Rio Grande, shrunken by years of drought and ever greater demand, no longer provides a reliable source of irrigation water. Part of the deficit is related to a simmering water conflict between Texas and Mexico stemming from a river sharing agreement signed on February 3, 1944 known as the “Treaty of the Utilization of Waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers and of the Rio Grande.” Under the treaty, Mexico is required to release 1.75 million acre-feet of water every five years to the U.S. from six tributaries that feed into the Rio Grande. (An acre-foot is roughly 326,000 gallons.) Ideally, Mexico would deliver an average annual amount of 350,000 acre-feet. In exchange, the U.S. delivers water from the Colorado River to Mexico.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality says that Mexico is behind on delivering the water under the terms of the treaty and owes the U.S. 471,000 acre-feet of water. According to June 2013 reporting in the Texas Tribune by Julian Aquilar, Mexico only provided 49 percent of its obligation in 2012 only 6 percent in 2013.

An interesting new battleground in the struggle for water in Texas is the fight for sewage treatment plant effluent. In a January 2014 article in the Texas Tribune, Neena Satija reported that San Antonio is seeking to declare ownership of its wastewater. Every year, the San Antonio Water System (SAWS) treats close to 33 billion gallons of wastewater and discharges it into the San Antonio River. Because Texas water law says all surface water is owned by the state, the city effectively cedes ownership of the effluent once it is released into the river. “What we’d like to do is to get authorization to retain ownership of that water, even after it’s put into the river,” said SAWS spokesman Greg Flores III. “We do own that asset. Our ratepayers own that asset.” But apportioned water users downstream from San Antonio’s wastewater treatment plant are ready to fight back. Bill West, general manager of the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority (GBRA), a water supplier and hydroelectric provider for 10 south Texas counties, said it would present a major challenge. For decades, the GBRA and companies including Dow Chemical have held water rights that depend on SAWS’ wastewater, he said. “In dry years, those water right holders use the majority of that water,” he added.

SAWS and GBRA have been scrapping over water supplies in various Texas river basins since 2005 when SAWS backed out of a planned collaboration. Even some legislators have said that San Antonio has been too aggressive in the hunt for new water sources in rural areas, according to a March 2014 report in the New York Times titled “Growth Tests San Antonio’s Conservation Culture.” “When San Antonio comes into the room, there’s definitely a reaction that I’ve noticed: ‘Who loses on this deal for the benefit of San Antonio?’ ” said State Representative Lyle Larson. This is an example of the golden rule of water supplies: Whomever has the gold, makes the rules.

Houston has also relied on reused wastewater effluent for decades. The Trinity River passes through the heart of Dallas and continues southeast another 200 miles through piney woods and past Houston before draining into Galveston Bay. Dallas returns much of the water it uses to the river in the form of treated wastewater. Downstream, Houston residents rely on that flow of reused water for municipal consumption. “Every drop of water that’s being consumed in Houston has been through the wastewater treatment plants in Dallas and Fort Worth,” said Andy Sansom, director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University.

California

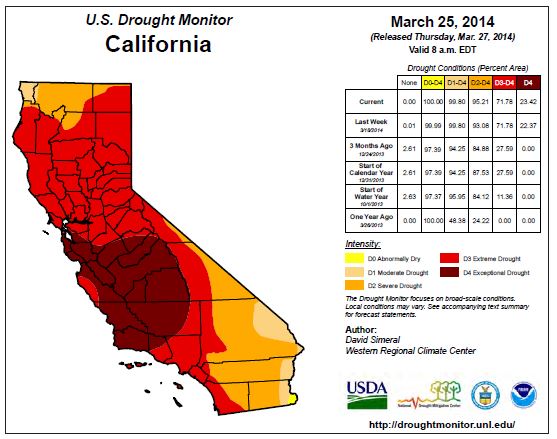

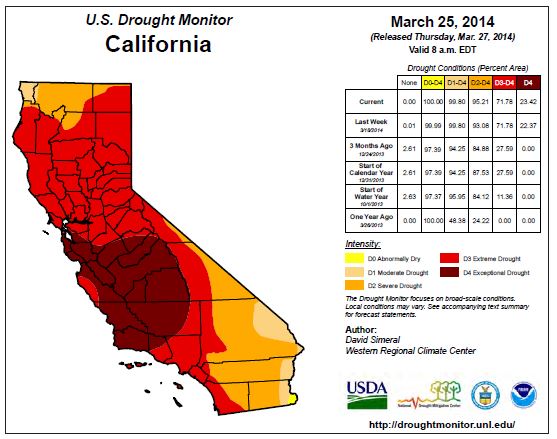

This year California is feeling the tightening grip of drought. In 119 years of hydrologic data, 2013 was the driest calendar year for the state of California. On January 17, 2014, California Governor, Jerry Brown, declared a drought state of emergency and directed state officials to take all necessary actions to prepare for drought conditions. “We can’t make it rain, but we can be much better prepared for the terrible consequences that California’s drought now threatens, including dramatically less water for our farms and communities and increased fires in both urban and rural areas,” said Governor Brown. “I’ve declared this emergency and I’m calling all Californians to conserve water in every way possible.”

Later the Governor remarked, “Every day this drought goes on we are going to have to tighten the screws on what people are doing.” The state’s growing predicament became glaring on January 31, 2014 when state officials announced that for the first time in its 54-year history, no water, none, would be released from a huge system of reservoirs to local agencies.

As of March 18, 2014, the California Department of Water Resources measured the statewide water content of the snowpack at only 26% of the average historical April 1st volume. This measurement is crucial because the end of March is when the snowpack is normally at its greatest extent and begins to melt, feeding streams and reservoirs. Snowpack is the source of about one-third of all the water used by California’s cities and farms. “We are on track for having the worst drought in 500 years,” said B. Lynn Ingram, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Berkeley.

Kate Galbraith, in a March 2014 column titled “America’s Axis of Drought,” on the news website the Daily Beast, noted some similarities between the two most populous states, California and Texas, during their driest years. Both are major agricultural states that do not regulate groundwater use at the state level. Both have published lists of mostly rural towns where the taps could run dry. And both experienced massive wildfires causing large amounts of property damage. But perhaps the biggest lesson from Texas is that severe droughts can drag on long past the time when the hills turn green. Kate Galbraith, in a March 2014 column titled “America’s Axis of Drought,” on the news website the Daily Beast, noted some similarities between the two most populous states, California and Texas, during their driest years. Both are major agricultural states that do not regulate groundwater use at the state level. Both have published lists of mostly rural towns where the taps could run dry. And both experienced massive wildfires causing large amounts of property damage. But perhaps the biggest lesson from Texas is that severe droughts can drag on long past the time when the hills turn green.

California’s San Joaquin Valley, or Central Valley, is an Eden where more than one quarter of the nation’s fruits and vegetables are grown. Peaches, plums, grapes, lettuce, almonds, strawberries, and hundreds of other crops are produced in abundance using irrigation water. With water, this is the best agricultural land in the world. Irrigation water is distributed throughout the fertile valley by the Central Valley Project, a tangle of aqueducts, pumps, canals and dams, which is the largest government water development project in the United States.

However, rights to irrigation water are not equitably distributed. As described in a March 2014 column in the New York Times by Mark Bittman titled, “Exploiting California’s Drought,” many farmers have a water supply contract with one of hundreds of water districts, granted when the state’s population was much smaller, water was plentiful, and environmental concerns ignored. These contracts boosted the economy at great cost to the environment, and they are ludicrously unfair. Some farmers pay $7 per acre-foot, others pay $200; some have to buy water on the open market, and cities generally pay over $1,000. Newer state regulations mandate the measurement of actual water use and a pricing system that is based in part on the amount of water used. “The regs don’t say that you have to use less water, but that you have to use it more efficiently,” said Doug Obegi, a staff attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

As the tenacious drought worsens, many farmers are receiving none of their federal water allocation. Some are pulling out their trees or crops or not bothering to plant at all. This year, about one-half million of California’s eight million acres of agricultural land will not be planted. While it is too early to tell how much the drought may push up household grocery bills, many economists forecast that consumers can expect to pay more for food later this year.

“I have experienced a really long career in this area, and my worry meter has never been this high,” said Tim Quinn, executive director of the Association of California Water Agencies in a New York Times article titled, “Severe Drought Has U.S. West Fearing Worst,” by Adam Nagourney and Ian Lovett. “We are talking historical drought conditions, no supplies of water in many parts of the state. My industry’s job is to try to make sure that these kind of things never happen. And they are happening.”

Business Challenges

It is not just farmers and cities that worry about reliable water supplies. Unreliable water supplies can also have a devastating effect on business development. Over 75 percent of the world’s biggest companies see water risks as critical, but most of these companies lack long-term water strategies, a KPMG sustainability report concluded. In a July 2013 article titled, “As drought spreads, firms could be up the creek,” on the business news website CNBC, Constance Gustke wrote that corporations with a global footprint are scrambling to address their water risk because shortages can quickly short-circuit business in developing regions. Water reliability is increasingly seen as a competitive edge. In the future, businesses will need to factor water availability—and quality—when searching for new manufacturing sites or face possible deficits. Worldwide, shortages will be dire in coming years. By 2030, there will be a 40 percent global shortfall between water demand and water supply, according to the World Economic Forum.

“Companies across the spectrum are facing water challenges. Water is becoming the silent currency,” said Giulio Boccaletti, managing director of global fresh water at Nature Conservancy.

What Then Shall We Do?

Indeed, what then shall we do? If drought turns out to be an ongoing condition in the American West, the “new normal,” and cities, business, and agriculture need a reliable and growing supply of water to prosper, what’s to be done? Some legislators think that praying for rain is the proper way to address the crisis. When faced with a crippling water shortage, praying is certainly understandable, but it is not really a good long-term strategy.

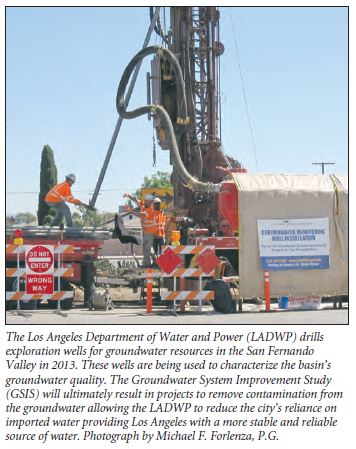

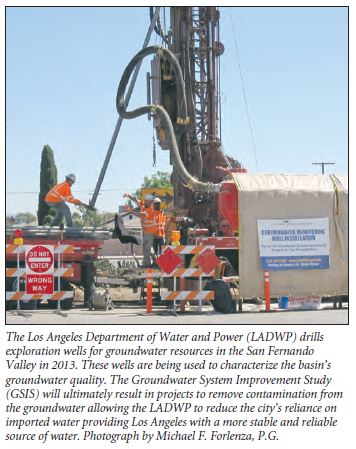

One developing water management strategy that many cities are studying is aquifer storage and recovery (ASR). Implementing this strategy involves storing water during times of surplus in aquifers to be recovered during periods of deficit. The benefits of underground water storage versus surface water storage are multiple: large dams and other engineered structures are not needed, extensive land acquisition is avoided, and loss of ecological habitats due to flooding is prevented leading to overall lower costs versus a surface reservoir. “It just makes so much more sense,” said Jim Lester, president of the Houston Advanced Research Center, a nonprofit research group. Additionally, water does not evaporate from storage when held in an aquifer. Evaporation can be serious problem in arid regions. Some reservoirs in western Texas lose more water each year into the air than is used by people.

After geological studies identify a suitable aquifer with the proper characteristics of porosity, permeability, and geometry, surface water is injected by wells into the formation for storage and later retrieval. In some cases, such in El Paso, treated wastewater can be stored for later use. Aquifers used for ASR ideally have a moderate level of salinity allowing the fresher stored water to rest atop the displaced saline water and be readily accessible.

ASR projects may face legal challenges. Utilities injecting water into an aquifer will want to ensure that the water is legally theirs to recover. In Texas, the “rule of capture” law means that anyone has a right to recover water under that person’s land. So even if a utility injected the water, in theory it could belong to someone else when it is withdrawn form a supply well.

Conservation is a strategy that can be implemented by any community to slow the growth of water demand. Conservation measures involving reduction of water losses during transmission and distribution, use of more efficient household appliances, and use of drought tolerant native plantings to reduce landscaping irrigation produce immediate benefits. Other near-term measures can be a switch to more efficient agricultural irrigation methods such as drip irrigation or developing strategic water pricing to more closely reflect the true value of the resource. Price is a very powerful motivator. When something costs more, people use less. Conservation is a strategy that can be implemented by any community to slow the growth of water demand. Conservation measures involving reduction of water losses during transmission and distribution, use of more efficient household appliances, and use of drought tolerant native plantings to reduce landscaping irrigation produce immediate benefits. Other near-term measures can be a switch to more efficient agricultural irrigation methods such as drip irrigation or developing strategic water pricing to more closely reflect the true value of the resource. Price is a very powerful motivator. When something costs more, people use less.

Longer-term strategies may employ evolving technologies like desalination of brackish groundwater, reuse of wastewater, or expanding the use of renewable energies such as solar which uses far less water per kilowatt generated than conventional power generation. All of these elements should be considered during long-term water planning to manage and diversify water sources.

But as drought grinds on across the American West, the time to act has come. As the old adage says, “Don’t wait until it is raining to fix the roof.” On second thought, if it is raining, go out and enjoy the blessing.

|

Fortunes have been made in Texas, Arizona, California, Nevada, and New Mexico in agriculture, ranching, mining, gaming, recreation, energy, and development. For many decades, fast-growing, sun-washed cities in the region attracted people seeking a place to start anew and prosper. Cheap land and available resources lured entrepreneurs, retirees, recreationists, and businesses to this arid land. This frenzy of growth was lubricated by seemingly limitless supplies of fresh water pumped from relict groundwater or transported across the baked landscape by vast government projects. This cheap supply kept electrical generating facilities humming, maintained verdant lawns and golf courses, filled shimmering reservoirs, and slaked the thirst of lush fields of cotton, grain, fruits, and vegetables.

Fortunes have been made in Texas, Arizona, California, Nevada, and New Mexico in agriculture, ranching, mining, gaming, recreation, energy, and development. For many decades, fast-growing, sun-washed cities in the region attracted people seeking a place to start anew and prosper. Cheap land and available resources lured entrepreneurs, retirees, recreationists, and businesses to this arid land. This frenzy of growth was lubricated by seemingly limitless supplies of fresh water pumped from relict groundwater or transported across the baked landscape by vast government projects. This cheap supply kept electrical generating facilities humming, maintained verdant lawns and golf courses, filled shimmering reservoirs, and slaked the thirst of lush fields of cotton, grain, fruits, and vegetables.

New Mexico

New Mexico

Kate Galbraith, in a March 2014 column titled “America’s Axis of Drought,” on the news website the Daily Beast, noted some similarities between the two most populous states, California and Texas, during their driest years. Both are major agricultural states that do not regulate groundwater use at the state level. Both have published lists of mostly rural towns where the taps could run dry. And both experienced massive wildfires causing large amounts of property damage. But perhaps the biggest lesson from Texas is that severe droughts can drag on long past the time when the hills turn green.

Kate Galbraith, in a March 2014 column titled “America’s Axis of Drought,” on the news website the Daily Beast, noted some similarities between the two most populous states, California and Texas, during their driest years. Both are major agricultural states that do not regulate groundwater use at the state level. Both have published lists of mostly rural towns where the taps could run dry. And both experienced massive wildfires causing large amounts of property damage. But perhaps the biggest lesson from Texas is that severe droughts can drag on long past the time when the hills turn green. Conservation is a strategy that can be implemented by any community to slow the growth of water demand. Conservation measures involving reduction of water losses during transmission and distribution, use of more efficient household appliances, and use of drought tolerant native plantings to reduce landscaping irrigation produce immediate benefits. Other near-term measures can be a switch to more efficient agricultural irrigation methods such as drip irrigation or developing strategic water pricing to more closely reflect the true value of the resource. Price is a very powerful motivator. When something costs more, people use less.

Conservation is a strategy that can be implemented by any community to slow the growth of water demand. Conservation measures involving reduction of water losses during transmission and distribution, use of more efficient household appliances, and use of drought tolerant native plantings to reduce landscaping irrigation produce immediate benefits. Other near-term measures can be a switch to more efficient agricultural irrigation methods such as drip irrigation or developing strategic water pricing to more closely reflect the true value of the resource. Price is a very powerful motivator. When something costs more, people use less.