From the Editor - October 2013 by Michael Forlenza

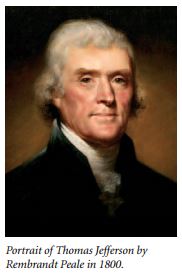

|

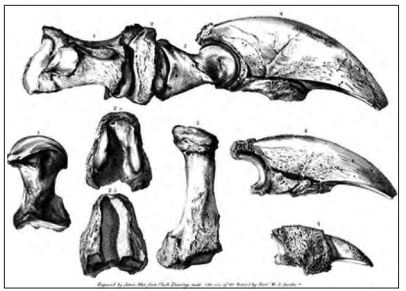

In the 18th century, most Europeans and Americans embraced a world view in which nature was seen as complete, full, and perfect, as created by God. Within this model, each species was as the creator made it and no species ever became extinct because such an event would destroy the perfection of nature. Toward the end of the 18th century, the concept that no species had ever become extinct was increasingly challenged by evidence from the fossil record. The developing science of geology was going through a revolution as the field transitioned from a series of casual observations of the natural world by gentlemen scholars to a rigorous science. In 1788, the Scottish physician James Hutton, published Theory of the Earth; or an Investigation of the Laws observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land upon the Globe in theTransactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.His work laid out the fundamental principles of geology postulating that erosion and sedimentation were part of continuing processes that had occurred throughout Earth’s history. Wit h t hes e precept s , he recognized the great age of the Earth. In the 18th century, most Europeans and Americans embraced a world view in which nature was seen as complete, full, and perfect, as created by God. Within this model, each species was as the creator made it and no species ever became extinct because such an event would destroy the perfection of nature. Toward the end of the 18th century, the concept that no species had ever become extinct was increasingly challenged by evidence from the fossil record. The developing science of geology was going through a revolution as the field transitioned from a series of casual observations of the natural world by gentlemen scholars to a rigorous science. In 1788, the Scottish physician James Hutton, published Theory of the Earth; or an Investigation of the Laws observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land upon the Globe in theTransactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.His work laid out the fundamental principles of geology postulating that erosion and sedimentation were part of continuing processes that had occurred throughout Earth’s history. Wit h t hes e precept s , he recognized the great age of the Earth.In the decades preceding the American Revolution and for a period afterwards, tales of strange and gigantic creatures roaming the interior of the barely charted North American continent made their way east. Thomas Jefferson avidly collected such accounts as they were important for his view of science. Jefferson believed that these accounts described undiscovered species of mastodons, mammoths, wooly rhinoceros, and huge predators. While Jefferson did not believe in extinction and may not have grasped the concept of deep time, he maintained a life-long interest in fossils. Because his interest in fossils was widely known, many people sent him unusual specimens of large bones found on the American frontier. Over many years he amassed a large collection of “mammoth” remains, which he displayed in the entrance hall of Monticello, his great house in Virginia.  So it was, that in 1799 that Colonel John Stuart sent Jefferson some bones of a huge mammal "of the clawed kind" that had been found in a cave in the Blue Mountains in Greenbrier County (presentday West Virginia) by workmen mining sodium nitrate. The bones consisted of parts of an upper and lower arm with extremely large claws at the end of each finger. Jefferson was fascinated. By careful comparisons with the anatomical accounts of other animals, he ultimately concluded the bones were those of a huge unknown cat of some sort "three times as large as the lion." So it was, that in 1799 that Colonel John Stuart sent Jefferson some bones of a huge mammal "of the clawed kind" that had been found in a cave in the Blue Mountains in Greenbrier County (presentday West Virginia) by workmen mining sodium nitrate. The bones consisted of parts of an upper and lower arm with extremely large claws at the end of each finger. Jefferson was fascinated. By careful comparisons with the anatomical accounts of other animals, he ultimately concluded the bones were those of a huge unknown cat of some sort "three times as large as the lion."Jefferson described this creature in his writings and named it Megalonyxor "great claw." In March 1797, he presented his findings to the American Philosophical Society under the title, A Memoir of the Discovery of Certain Bones of an Unknown Quadruped, of the Clawed Kind, in the Western Part of Virginia. Many consider this to be the first scientific report on paleontology published in the United States. Before Thomas Jefferson was elected as the third president of the United States of America, he was elected president of the American Philosophical Society in 1797. He held the office of president of the American Philosophical Society until 1814, throughout serving two terms as the President of the United States.  The American Philosophical Society was founded in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin in 1743. The American Philosophical Society website (www.amphilsoc.org) states that the society is "an eminent scholarly organization of international reputation, the American Philosophical Society promotes useful knowledge in the sciences and humanities through excellence in scholarly research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and community outreach. This country’s first learned society, the APS has played an important role in American cultural and intellectual life for over 250 years." The American Philosophical Society was founded in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin in 1743. The American Philosophical Society website (www.amphilsoc.org) states that the society is "an eminent scholarly organization of international reputation, the American Philosophical Society promotes useful knowledge in the sciences and humanities through excellence in scholarly research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and community outreach. This country’s first learned society, the APS has played an important role in American cultural and intellectual life for over 250 years."Benjamin Franklin advocated for the society by noting that, “the first drudgery of settling new colonies is now pretty well over and there are many in every province in circumstances that set them at ease, and afford leisure to cultivate the finer arts, and improve the common stock of knowledge.” Early members included doctors, lawyers, clergymen, and merchants interested in science, and also many learned artisans and tradesmen like Franklin. Many founders of the republic were members: George Washington, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Rush, James Madison, and John Marshall; as were many distinguished foreigners: Lafayette, von Steuben, and Kosciusko. Later, illustrious names were continually added to the membership roster, reflecting the society’s scope. These included Charles Darwin, Robert Frost, Louis Pasteur, Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz, John James Audubon, Linus Pauling, Margaret Mead, Maria Mitchell, and Thomas Edison. Thomas Jefferson’s contributions to the study of geology in the United States were considerable. He established the United States Geodetic Survey and the United States Coast Survey (1807), the forerunner of the United States Geological Survey. Jefferson proposed the adoption of the Public Land Survey System that was the foundation of the township and range system familiar to most geologists. He sponsored the Corps of Discovery Expedition in 1804 to the newly-acquired Louisiana Purchase under the command of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark and encouraged the search for minerals and fossils. Jefferson very much hoped that the expedition would find evidence of both living mastodons and Megalonyxin the vast unexplored American West beyond the Appalachian Mountains: "In the present interior of our continent there is surely space and range enough for elephants and lions, if in that climate they could subsist; and for the mammoth and megalonyxes who may subsist there. Our entire ignorance of the immense country to the West and North-West, and of its contents, does not authorise us so say what is does not contain."

In his 1951 article Thomas Jefferson and the Geological Sciences, Joel Martin Halpern, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Massachusetts, noted that Jefferson, like scientific thinkers before him, puzzled with the problem of marine fossils in the rocks on mountain tops. While studying fossil shells found in the Andes of South America at an elevation of 15,000 feet above sea level, Jefferson was not willing to accept this as evidence of a global, biblical deluge. Jefferson observed that there was no source of water that could cover the Earth to a depth of 15,000 feet. He calculated that converting the entire atmosphere to liquid would cover the globe only to a depth of 35 feet. Jefferson concluded that the deluge hypothesis was "unsatisfactory and we must be content to acknowledge that this great phenomenon is yet unsolved." |

America's First Paleontologist: Thomas Jefferson and Megalonyx

America's First Paleontologist: Thomas Jefferson and Megalonyx