|

After telling someone that you are a geologist, they will reply something like: “Oh, that is something to do with rocks.” Well, yes, OK. Discussion of the topic generally ends at that point. But one can hardly blame the non-geologist for his vague sense of what a geologist does. The world of earth science is arcane to most people. And there are few prominent geologists communicating with the public through the media about the professional contributions of geoscientists or acting as champions of the science.

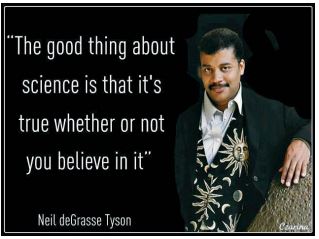

Other sciences have their superstars. Cosmologists, astrophysicists, and astronomers have their popular heroes who are known to a wide public audience and appear regularly on television and in the news. These include the late Carl Sagan, Stephen Hawking, and Neil deGrasse Tyson. The affable Dr. Tyson is an astrophysicist, author, radio personality, science communicator, the Frederick P. Rose Director of the Hayden Planetarium, and a research associate in the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. From 2006 to 2011, he hosted the educational science television show NOVA ScienceNowon PBS and has been a frequent guest on The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, and Jeopardy!. Dr. Tyson is the host of the television series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, a 2014 update to Carl Sagan’s Cosmos: A Personal Voyage.

Physicists have also had media favor ites like Albert Einstein. Chemists, biologists, physicists, and medical researchers get their moment in the spotlight each year during the awarding of the Nobel prizes. Geologists labor in relative obscurity. ites like Albert Einstein. Chemists, biologists, physicists, and medical researchers get their moment in the spotlight each year during the awarding of the Nobel prizes. Geologists labor in relative obscurity.

Importantly, several contentious issues that appear almost daily in the news are related to the geological sciences. These involve climate change, energy, teaching evolution and creation science, hydraulic fracturing, drought, and, recently, landslides and tsunamis. Yet, there are no prominent geologists providing insight on these matters.

Too often there is no input from trained geoscientists in the discussion of important earth science topics in the public discourse, leaving the media spotlight to untrained politicians and activists. Scott Tinker, a geologist and highly-credentialed energy expert who heads the Bureau of Economic Geology at The University of Texas and is a professor at the Jackson School of Geosciences, is one geoscientist who has made an effort to communicate energy issues to the public through the Switch Energy Project. The project released the documentary film Switchin 2012 featuring Dr. Tinker as the narrator. But these contributions have barely registered in the public debate.

So how does the general public perceive geology and geologists? How are this science and these scientists portrayed in the popular culture and media of television, movies, and books?

Common Perception

The most common public perception of a geologist is a guy, or gal, with an inclination toward field clothes (hiking boots, jeans, plaid shirt), who carries a rock hammer in one hand and wears a hand lens around the neck. These rock hounds are rugged, bearded (male only) mavericks, who enjoy many drinks, and are more comfortable outdoors and outside of polite company. Fastidious grooming and social customs are largely uninteresting to these hardy individuals as they are preoccupied with pondering esoteric concepts such as subduction, diagenesis, phase diagrams, illitesmectite alteration, acoustical impedance variations, contourite deposition, and high-temperature pyrolosis.

Most geologists may recognize some of these perceived characteristics in themselves, and the whole package was probably true of many geologists at some point in their development. But where does this perception come from and how accurate is it?

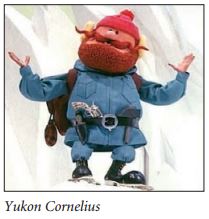

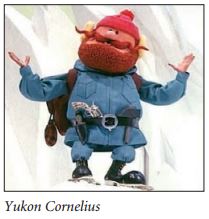

An early portrayal of this type of geologist, familiar to children, was the rambunctious Yukon Cornelius in the 1964 television Christmas classic, the stop-motion animated Rudolph the RedNosed Reindeer. Y. Cornelius was a rough and capable prospector who could taste precious metals and ores on his rock hammer. He was heavily bearded, wore field boots and clothes, had a confident and optimistic attitude, and even carried a pistol in his belt. He was a pretty cool geologist, but not really an accurate depiction of a modern geologist. An early portrayal of this type of geologist, familiar to children, was the rambunctious Yukon Cornelius in the 1964 television Christmas classic, the stop-motion animated Rudolph the RedNosed Reindeer. Y. Cornelius was a rough and capable prospector who could taste precious metals and ores on his rock hammer. He was heavily bearded, wore field boots and clothes, had a confident and optimistic attitude, and even carried a pistol in his belt. He was a pretty cool geologist, but not really an accurate depiction of a modern geologist.

Television

Television has had very few accurate portrayals of geologists, whether fictional or non-fictional. Doctors, detectives, and lawyers and their professional activities have been portrayed countless times in television series. Even ad men, paper salespersons, and astrophysicists have been portrayed in comedy and drama series. Maybe geologists aren’t that interesting.

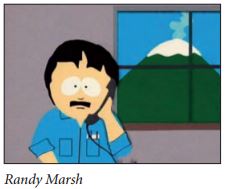

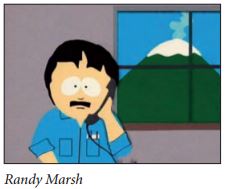

Perhaps the most famous geologist on television is not even a real person. In the 17 seasons of the raunchy and ribald animated television series on Comedy Central, South Parkhas featured a geologist as one of the main characters. Randy Marsh, the father of Stan, is portrayed as a somewhat quirky (OK, a lot quirky) earth scientist with a love of beer. Randy is named after South Park creator Trey Parker’s own father, Randy Parker, who was a geologist. In Randy’s first appearance in the series, he is monitoring a seismometer in the episode “Volcano.” Randy has been portrayed as having this profession for the entire duration of the series. He carries a few pens in one of the two front pockets on his light blue, collared, button-down shirt, and he wears dark gray pants. He has mentioned that he attended college and it has been indicated that he holds a doctorate.

In the hit comedy television series The Big Bang Theoryon CBS, Dr. Sheldon Cooper, the socially awkward genius theoretical physicist, often disparages the other “softer” sciences. In Episode 1 of Season 5, Dr. Cooper and his physicist colleagues take on the geology department in a spirited paintball contest in the woods. At a critical moment, Dr. Cooper charges into the open and shouts, “Geology isn’t a REAL science!” This draws the wrath of the earth scientists who unleash a multi-colored paintball fusillade in retaliation. Filmed in slow motion, the scene is an homage to the Sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe) death scene from the movie Platoon. Later in the series, Dr. Cooper remarks, “Geology is the Kardashians of science.” Ouch. In the hit comedy television series The Big Bang Theoryon CBS, Dr. Sheldon Cooper, the socially awkward genius theoretical physicist, often disparages the other “softer” sciences. In Episode 1 of Season 5, Dr. Cooper and his physicist colleagues take on the geology department in a spirited paintball contest in the woods. At a critical moment, Dr. Cooper charges into the open and shouts, “Geology isn’t a REAL science!” This draws the wrath of the earth scientists who unleash a multi-colored paintball fusillade in retaliation. Filmed in slow motion, the scene is an homage to the Sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe) death scene from the movie Platoon. Later in the series, Dr. Cooper remarks, “Geology is the Kardashians of science.” Ouch.

Movies

The movies have not been particularly generous to geologists. While the movie geologist is usually geeky and anti-social, there is a remarkably long list of films with geological plot points and characters. Dr. Catherine A. Riihimaki taught the course Geology 197: Geology in the Movies while at Drew University in 2009. The syllabus for the course indicated that the lectures included screenings of: The Shawshank Redemption, Spitfire Grill, Dante’s Peak, Volcano, Earthquake, Superman, Aftershock: Earthquake in New York, The Core, Journey to the Center of the Earth, Alien Hunter, Evolution, Planet of the Apes, Deep Impact, Armageddon, Jurassic Park, The Abyss, Finding Nemo, Perfect Storm, Twister, Ice Age, Waterworld, The Day after Tomorrow, Vertical Limit, Boa, Red Planet,and Mission to Mars.

Needless to say, most of these portrayals of geology and geologists are rather light on the science. So much so, that even second year geology students are likely to roll their eyes and become exasperated at some of the science gaffes and fabrications. Needless to say, most of these portrayals of geology and geologists are rather light on the science. So much so, that even second year geology students are likely to roll their eyes and become exasperated at some of the science gaffes and fabrications.

The Core, a 2003 disaster film with mild box office success, was particularly ambitious in its depiction of pseudo-science. A series of disturbances caused by instability in the Earth’s magnetic field lead geologists to learn that the Earth’s molten core has stopped rotating. Within a year, the Earth’s magnetic field will collapse, leaving the planet vulnerable to solar radiation. The geologists develop a plan to use a nuclear powered vessel, the Virgil, with a high frequency-pulse laser to bore into the Earth’s core and plant a series of nuclear charges at precise points to restart the core’s motion and restore the field. Launched through the Marianas Trench, the Virgilaccidentally drills through a gigantic empty geode, damaging the lasers when it lands at its base and cracking the geode’s structure, causing magma to flow in. The crew repair and restart the laser array in time, but a crewman is killed by a falling crystal shard while returning to the ship. As the Virgilcontinues, it clips a huge diamond that breaches the hull of the last compartment. A crewman sacrifices himself to save the nuclear launch codes before the compartment is crushed by extreme pressure.

When the Virgileventually reaches the molten core, new data reveal a flaw in the plan. The outer layer of the core is less dense than anticipated and the planned explosions cannot generate the needed power. After some calculations, they decide that by splitting their nuclear weapons into the remaining compartments and jettisoning each at specific distances, they can create a “ripple effect,” where the power of each bomb will push against the blast of the next, generating the needed energy wave. Meanwhile, on the surface, the public becomes aware of the problems at the Earth’s core after super storms start to lash the world, causing a worldwide panic.

Coincidently, the team l earns of the top-secret project “DESTINI” (Deep Earth Seismic Trigger INItiative), which was designed as a weapon to propagate earthquakes through the Earth’s core. But in its first activation, the weapon unintentionally stopped the core’s rotation instead. The government has plans to use it again to attempt a restart of the core if the mission fails. earns of the top-secret project “DESTINI” (Deep Earth Seismic Trigger INItiative), which was designed as a weapon to propagate earthquakes through the Earth’s core. But in its first activation, the weapon unintentionally stopped the core’s rotation instead. The government has plans to use it again to attempt a restart of the core if the mission fails.

The triggered explosions successfully restart the core’s rotation. The crew uses the heat and pressure from the wavefront to enable the vessel to escape the core. The Virgilbreaks through the crust underwater, leaving them on the ocean floor without power or communications. The crew uses the remaining power to activate a weak sonar beacon attracting a nearby whale pod. Rescuers are able to trace the whale songs to locate the Virgil.

Dante’s Peak, a somewhat more plausible geology story, features hunky Pierce Brosnan as Dr. Harry Dalton, a vulcanologist with the United States Geological Survey. Dr. Dalton arrives at the Washington state countryside area, named Dante’s Peak after a long dormant volcano, which has recently been named the second most desirable place to live in America and discovers that Dante’s Peak, may wake up at any moment. Matt Herod, on his geology blog GeoSphere, provides this movie analysis: “There is not a whole lot of actual geology in Dante’s Peak, but despite that Pierce delivers an excellent performance as the ‘whistle-blowing geologist’ that no one wants to listen to until it is too late. It is also another great media stereotype of geologists as nerdy, but rugged, people who care more about rocks, water and gases than people.” Dante’s Peak, a somewhat more plausible geology story, features hunky Pierce Brosnan as Dr. Harry Dalton, a vulcanologist with the United States Geological Survey. Dr. Dalton arrives at the Washington state countryside area, named Dante’s Peak after a long dormant volcano, which has recently been named the second most desirable place to live in America and discovers that Dante’s Peak, may wake up at any moment. Matt Herod, on his geology blog GeoSphere, provides this movie analysis: “There is not a whole lot of actual geology in Dante’s Peak, but despite that Pierce delivers an excellent performance as the ‘whistle-blowing geologist’ that no one wants to listen to until it is too late. It is also another great media stereotype of geologists as nerdy, but rugged, people who care more about rocks, water and gases than people.”

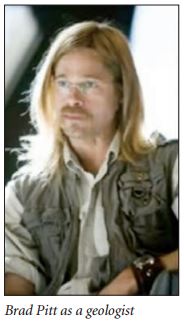

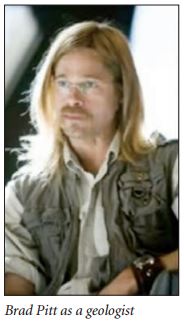

Another interesting cinematic portrayal of a geologist is found in the caper Ocean’s Thirteen. To plant a camera in the casino boss’s office, Brad Pitt pretends to be a geologist with a warning about a hidden fault line under the building. Mr. Pitt’s appearance is a bit of a spoof, an over-exaggeration of how Hollywood thinks that the public thinks that a geologist would look. He, of course, is bespectacled, dressed in a battered field clothes (vest and shorts), and sports a very large leather watch band. He is somewhat unkempt with scraggly facial hair. Another interesting cinematic portrayal of a geologist is found in the caper Ocean’s Thirteen. To plant a camera in the casino boss’s office, Brad Pitt pretends to be a geologist with a warning about a hidden fault line under the building. Mr. Pitt’s appearance is a bit of a spoof, an over-exaggeration of how Hollywood thinks that the public thinks that a geologist would look. He, of course, is bespectacled, dressed in a battered field clothes (vest and shorts), and sports a very large leather watch band. He is somewhat unkempt with scraggly facial hair.

One of the better depictions of a geologist in movies is in the 1986 French language film Manon des Sources(Manon of the Spring). A geologist arrives in a remote Provencal town to help the residents in dealing with the loss of the flowing spring which provided their water supply. In a brief scene, the geologist goes into a technical talk on the local geology at a town meeting. The discussion goes way over the head of the frustrated populace before he abruptly packs up and leaves without providing any real help.

Paleontologists Paleontologists

Perhaps the most well-known geologists today are the paleontologists. Dinosaurs, and the study of dinosaurs, have entered the mainstream. Kids love dinosaurs. This is a good thing. Children are very serious about the difference between an Apatosaurus and a Brontosaurus. Many children disappoint their grandparents at storybook time when they pick out the Giant Golden Book of Dinosaursto read rather than Charlotte’s Webor Treasure Island.

Two of the most widely-known paleontologists today are Robert Bakker and Jack Horner. Probably no paleontologist alive today has had as much of an impact on popular culture as Robert Bakker. Dr. Bakker was one of the technical advisers for the original Jurassic Parkmovie and the inspiration of a character in one of the sequels (The Lost World).

For over two decades, Robert H. Bakker has been the leading proponent of the theory that dinosaurs were warm-blooded, rather than cold-blooded like modern lizards. His ideas were presented in his 1986 book The Dinosaur Heresies. Not all scientists are convinced by Dr. Bakker’s theories, but he’s sparked a vigorous debate about dinosaur metabolism and dinosaur physiology.

To many people, Jack Horner is most famous as the inspiration for Sam Neill’s character in Jurassic Park. However, Dr. Horner is best known among paleontologists for his discoveries of the extensive nesting grounds of the duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura (“good mother lizard’) which cared for their young. The fossilized eggs and burrows at the nesting grounds gave paleontologists an unusually detailed glimpse of the family life of duck-billed dinosaurs. The author of numerous popular books, Dr. Horner has remained at the forefront of paleontological research. I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Horner in 1982 while we were both working on coincident field projects studying the Triassic redbeds in Nova Scotia.

Geologists and Beer Geologists and Beer

One facet of the public image of geologists is undoubtedly accurate. Geologists are well-known lovers of malted beverages. It has even been postulated that geologists are the only known “alcohol-based life form.” On my first day of graduate school at the University of Massachusetts, I was advised by a professor of structural geology and a professor of sedimentary petrography that I should make a point of attending the weekly “Safety Committee Meeting,” held on Fridays at 3:30 p.m. Their case for attending a safety committee meeting did not seem that strong, but I went anyway. Well, the only part of the gathering that had anything to do with safety was instructions on how to not injure one’s hand while removing the twist-off beer bottle caps. I was soon introduced to the combination-locked beer refrigerator in the basement rock laboratory. (Hint: the combination was cobalt, phosphorus, chlorine.)

In a 2009 article in Wiredmagazine, Betsy Mason explored the unusually affectionate connection between geologists and beer. For her research, she visited the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, the largest gathering of earth scientists in the world. At the meeting, starting at 3:30 p.m. each day, beer flows nonstop for an hour and a half at 10 stations. AGU organizers report that they go through about 175 kegs during the week. At the Thirsty Bear, the brewpub closest to the Moscone Convention Center where the meeting is held every December, the wait staff claims that this is the busiest week of the year. So, what is the nature of this sudsy bond?

The most popular theory, based on Ms. Mason’s interviews with the conference attendees, was that the connection has something to do with the amount of time spent outside doing fieldwork. “When it’s hot, and you’ve been hiking all day carrying 50 pounds of rocks, do you want a Merlot?” asked thermochronologist Jim Metcalf of Syracuse University. “No.” The most popular theory, based on Ms. Mason’s interviews with the conference attendees, was that the connection has something to do with the amount of time spent outside doing fieldwork. “When it’s hot, and you’ve been hiking all day carrying 50 pounds of rocks, do you want a Merlot?” asked thermochronologist Jim Metcalf of Syracuse University. “No.”

Geologists have been known to go to great lengths to chill their beer in the field as well. A cold stream, a glacier or a patch of snow is handy, but many field areas are hot, dry, and dusty. While doing fieldwork in Mongolia, geologist Cari Johnson of the University of Utah and her colleagues cooled their beer with evaporation by wrapping the cans in toilet paper, pouring water on the paper and letting the persistent wind dry the cans.

Another theory is that beer makes for better science, that the consumption of beer allows geoscientists to better conceptualize what cannot be seen. A third theory offered up in various forms was that beer is simply part of the geosciences culture, a tradition that has been handed down from advisor to student for generations. “It’s accepted and encouraged to drink beer,” said geologist Cindy Martinez of the American Geological Institute. “Other scientists like beer, but it’s not necessarily socially acceptable to have your scientific meetings revolve around beer.” “I started getting on to wine and other stuff for a while, but I became an outcast among my geology friends,” said geologist Laura Webb of the University of Vermont. ”So I had to re-train myself to drink brew.” Supporting the culture theory is the observation that earth science departments at academic institutions across the world almost invariably have a weekly get-together of some sort that revolves around beer.

I have a different theory about why geologists and beer go together. The connection seems to be not so much the science, but in the type of person who is drawn to the earth sciences. That type of person, casual, informal, different thinking, and sociable, also has a natural inclination to enjoy the consumption of beer and the open forum to exchange ideas.

Literature

Books are one media format that has been particularly good for geologists. Besides the previously mentioned paleontologists, two writers have risen to prominence in the last 20 or 30 years, writing well-received and best-selling books explaining the geological sciences. They are John McPhee and Simon Winchester. Even though neither man is a geologist by training, they share an admiration and fascination for the Earth, earth processes, and those who study them. Their works are engagingly written and approachable by non-scientists, providing enlightenment about the wonders of our planet’s lithosphere. These books are well-researched and have the depth of narrative to interest geologists.

John McPhee is widely considered one of the pioneers of creative nonfiction. He is a four-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in the category General Nonfiction and won that award on the fourth occasion in 1999. In 2008, he received the George Polk Career Award for his “indelible mark on American journalism during his nearly half-century career.” Since 1974, Mr. McPhee has been the Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton University. John McPhee is widely considered one of the pioneers of creative nonfiction. He is a four-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in the category General Nonfiction and won that award on the fourth occasion in 1999. In 2008, he received the George Polk Career Award for his “indelible mark on American journalism during his nearly half-century career.” Since 1974, Mr. McPhee has been the Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton University.

Starting his writing career at Timemagazine, Mr. McPhee later began a long association with The New Yorkermagazine beginning in 1965 that continues to the present. Many of his twenty-nine books include material originally written for The New Yorker. His books pertaining to geology include: Basin and Range (1981), In Suspect Terrain(1983), Rising from the Plains(1986), Assembling California(1993), and Annals of the Former World(1998), for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1999.

The 696-page compilation, Annals of the Former World, is a summary of Mr. McPhee’s numerous geological explorations along a cross section of North America following Interstate 80 from New York to California. This opus is his paean to geology and earth scientists. His works are known for their well-crafted prose. “As in any McPhee work, there are gemlike sentences, richly rhythmic paragraphs, nicely burnished synecdoches, metaphors as pungent as wasabi and, behind those felicities, vast amounts of painstaking research,” noted David Quammen in his New York Timesreview.

Simon Winchester, Order of the British Empire (OBE), is a British-born author and journalist who resides in the United States. During his career at The Guardian, Mr. Winchester covered numerous significant events, including Bloody Sunday and the Watergate scandal. As an author, Winchester has written or contributed to more than a dozen non-fiction books and his articles have appeared in several travel publications, including Condé Nast Traveler, Smithsonian Magazine, and National Geographic. Simon Winchester, Order of the British Empire (OBE), is a British-born author and journalist who resides in the United States. During his career at The Guardian, Mr. Winchester covered numerous significant events, including Bloody Sunday and the Watergate scandal. As an author, Winchester has written or contributed to more than a dozen non-fiction books and his articles have appeared in several travel publications, including Condé Nast Traveler, Smithsonian Magazine, and National Geographic.

Mr. Winchester has written three books on geological subjects. These are The Map That Changed the World(2001), Krakatoa, the Day the Earth Exploded: August 27, 1883(2003), and A Crack at the Edge of the World(2005). The Map That Changed the Worldis the story of William Smith, the orphaned son of an English country blacksmith, who became determined to create the world’s first geological map. William Smith’s map of the geology of England, Wales, and southern Scotland was published in 1815 and became one of the foundational blocks of modern geology. Krakatoa examines the world-changing effects of the catastrophic volcanic eruption off the coast of Java. The Crack in the Edge of the World is based on the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that leveled the city symbolic of America’s relentless western expansion. This book also provides an informative look at the tectonic forces and tumultuous subterranean world that produce earthquakes.

Summary

This informal survey suggests that the geologist is largely a stranger in popular culture and not well understood by the media. Some laypersons may imagine that the work of geologists is similar to being a pre-schooler. If it is a nice day, everyone goes outside to play and climb on rocks or have a field trip. If the weather is bad, everyone stays inside and does drawings with their colored pencils. Make sure to stay inside the lines!

What can we do about this? We can all make an effort to share what we know about our venerable science with interested people and provide perspective on issues that involve the geosciences. Visiting schools to talk to students about the important contributions geologists make to society is a great way to catch a young person’s imagination. It is time for geology and geologists to have their time in the spotlight.

So, the next time you are in a tavern enjoying a frosty beer after a long day at the hadrosaur dig and someone comes in screaming, “Oh, my god, a huge fissure spewing andesitic lava has triggered a lahar that is coming straight for us!,” shake the dust off of your field vest, take your boots off the table, grab your rock hammer, and shout, “Stand back, I am geologist, dammit!”

|

ites like Albert Einstein. Chemists, biologists, physicists, and medical researchers get their moment in the spotlight each year during the awarding of the Nobel prizes. Geologists labor in relative obscurity.

ites like Albert Einstein. Chemists, biologists, physicists, and medical researchers get their moment in the spotlight each year during the awarding of the Nobel prizes. Geologists labor in relative obscurity. An early portrayal of this type of geologist, familiar to children, was the rambunctious Yukon Cornelius in the 1964 television Christmas classic, the stop-motion animated Rudolph the RedNosed Reindeer. Y. Cornelius was a rough and capable prospector who could taste precious metals and ores on his rock hammer. He was heavily bearded, wore field boots and clothes, had a confident and optimistic attitude, and even carried a pistol in his belt. He was a pretty cool geologist, but not really an accurate depiction of a modern geologist.

An early portrayal of this type of geologist, familiar to children, was the rambunctious Yukon Cornelius in the 1964 television Christmas classic, the stop-motion animated Rudolph the RedNosed Reindeer. Y. Cornelius was a rough and capable prospector who could taste precious metals and ores on his rock hammer. He was heavily bearded, wore field boots and clothes, had a confident and optimistic attitude, and even carried a pistol in his belt. He was a pretty cool geologist, but not really an accurate depiction of a modern geologist. In the hit comedy television series The Big Bang Theoryon CBS, Dr. Sheldon Cooper, the socially awkward genius theoretical physicist, often disparages the other “softer” sciences. In Episode 1 of Season 5, Dr. Cooper and his physicist colleagues take on the geology department in a spirited paintball contest in the woods. At a critical moment, Dr. Cooper charges into the open and shouts, “Geology isn’t a REAL science!” This draws the wrath of the earth scientists who unleash a multi-colored paintball fusillade in retaliation. Filmed in slow motion, the scene is an homage to the Sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe) death scene from the movie Platoon. Later in the series, Dr. Cooper remarks, “Geology is the Kardashians of science.” Ouch.

In the hit comedy television series The Big Bang Theoryon CBS, Dr. Sheldon Cooper, the socially awkward genius theoretical physicist, often disparages the other “softer” sciences. In Episode 1 of Season 5, Dr. Cooper and his physicist colleagues take on the geology department in a spirited paintball contest in the woods. At a critical moment, Dr. Cooper charges into the open and shouts, “Geology isn’t a REAL science!” This draws the wrath of the earth scientists who unleash a multi-colored paintball fusillade in retaliation. Filmed in slow motion, the scene is an homage to the Sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe) death scene from the movie Platoon. Later in the series, Dr. Cooper remarks, “Geology is the Kardashians of science.” Ouch. Needless to say, most of these portrayals of geology and geologists are rather light on the science. So much so, that even second year geology students are likely to roll their eyes and become exasperated at some of the science gaffes and fabrications.

Needless to say, most of these portrayals of geology and geologists are rather light on the science. So much so, that even second year geology students are likely to roll their eyes and become exasperated at some of the science gaffes and fabrications. earns of the top-secret project “DESTINI” (Deep Earth Seismic Trigger INItiative), which was designed as a weapon to propagate earthquakes through the Earth’s core. But in its first activation, the weapon unintentionally stopped the core’s rotation instead. The government has plans to use it again to attempt a restart of the core if the mission fails.

earns of the top-secret project “DESTINI” (Deep Earth Seismic Trigger INItiative), which was designed as a weapon to propagate earthquakes through the Earth’s core. But in its first activation, the weapon unintentionally stopped the core’s rotation instead. The government has plans to use it again to attempt a restart of the core if the mission fails. Dante’s Peak, a somewhat more plausible geology story, features hunky Pierce Brosnan as Dr. Harry Dalton, a vulcanologist with the United States Geological Survey. Dr. Dalton arrives at the Washington state countryside area, named Dante’s Peak after a long dormant volcano, which has recently been named the second most desirable place to live in America and discovers that Dante’s Peak, may wake up at any moment. Matt Herod, on his geology blog GeoSphere, provides this movie analysis: “There is not a whole lot of actual geology in Dante’s Peak, but despite that Pierce delivers an excellent performance as the ‘whistle-blowing geologist’ that no one wants to listen to until it is too late. It is also another great media stereotype of geologists as nerdy, but rugged, people who care more about rocks, water and gases than people.”

Dante’s Peak, a somewhat more plausible geology story, features hunky Pierce Brosnan as Dr. Harry Dalton, a vulcanologist with the United States Geological Survey. Dr. Dalton arrives at the Washington state countryside area, named Dante’s Peak after a long dormant volcano, which has recently been named the second most desirable place to live in America and discovers that Dante’s Peak, may wake up at any moment. Matt Herod, on his geology blog GeoSphere, provides this movie analysis: “There is not a whole lot of actual geology in Dante’s Peak, but despite that Pierce delivers an excellent performance as the ‘whistle-blowing geologist’ that no one wants to listen to until it is too late. It is also another great media stereotype of geologists as nerdy, but rugged, people who care more about rocks, water and gases than people.” Another interesting cinematic portrayal of a geologist is found in the caper Ocean’s Thirteen. To plant a camera in the casino boss’s office, Brad Pitt pretends to be a geologist with a warning about a hidden fault line under the building. Mr. Pitt’s appearance is a bit of a spoof, an over-exaggeration of how Hollywood thinks that the public thinks that a geologist would look. He, of course, is bespectacled, dressed in a battered field clothes (vest and shorts), and sports a very large leather watch band. He is somewhat unkempt with scraggly facial hair.

Another interesting cinematic portrayal of a geologist is found in the caper Ocean’s Thirteen. To plant a camera in the casino boss’s office, Brad Pitt pretends to be a geologist with a warning about a hidden fault line under the building. Mr. Pitt’s appearance is a bit of a spoof, an over-exaggeration of how Hollywood thinks that the public thinks that a geologist would look. He, of course, is bespectacled, dressed in a battered field clothes (vest and shorts), and sports a very large leather watch band. He is somewhat unkempt with scraggly facial hair. Paleontologists

Paleontologists Geologists and Beer

Geologists and Beer The most popular theory, based on Ms. Mason’s interviews with the conference attendees, was that the connection has something to do with the amount of time spent outside doing fieldwork. “When it’s hot, and you’ve been hiking all day carrying 50 pounds of rocks, do you want a Merlot?” asked thermochronologist Jim Metcalf of Syracuse University. “No.”

The most popular theory, based on Ms. Mason’s interviews with the conference attendees, was that the connection has something to do with the amount of time spent outside doing fieldwork. “When it’s hot, and you’ve been hiking all day carrying 50 pounds of rocks, do you want a Merlot?” asked thermochronologist Jim Metcalf of Syracuse University. “No.” John McPhee is widely considered one of the pioneers of creative nonfiction. He is a four-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in the category General Nonfiction and won that award on the fourth occasion in 1999. In 2008, he received the George Polk Career Award for his “indelible mark on American journalism during his nearly half-century career.” Since 1974, Mr. McPhee has been the Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton University.

John McPhee is widely considered one of the pioneers of creative nonfiction. He is a four-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in the category General Nonfiction and won that award on the fourth occasion in 1999. In 2008, he received the George Polk Career Award for his “indelible mark on American journalism during his nearly half-century career.” Since 1974, Mr. McPhee has been the Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton University. Simon Winchester, Order of the British Empire (OBE), is a British-born author and journalist who resides in the United States. During his career at The Guardian, Mr. Winchester covered numerous significant events, including Bloody Sunday and the Watergate scandal. As an author, Winchester has written or contributed to more than a dozen non-fiction books and his articles have appeared in several travel publications, including Condé Nast Traveler, Smithsonian Magazine, and National Geographic.

Simon Winchester, Order of the British Empire (OBE), is a British-born author and journalist who resides in the United States. During his career at The Guardian, Mr. Winchester covered numerous significant events, including Bloody Sunday and the Watergate scandal. As an author, Winchester has written or contributed to more than a dozen non-fiction books and his articles have appeared in several travel publications, including Condé Nast Traveler, Smithsonian Magazine, and National Geographic.