From the Editor - November 2013 by Michael Forlenza

|

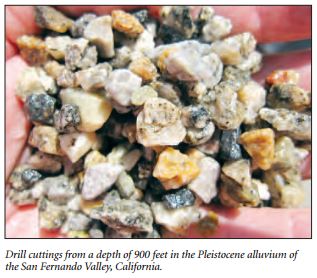

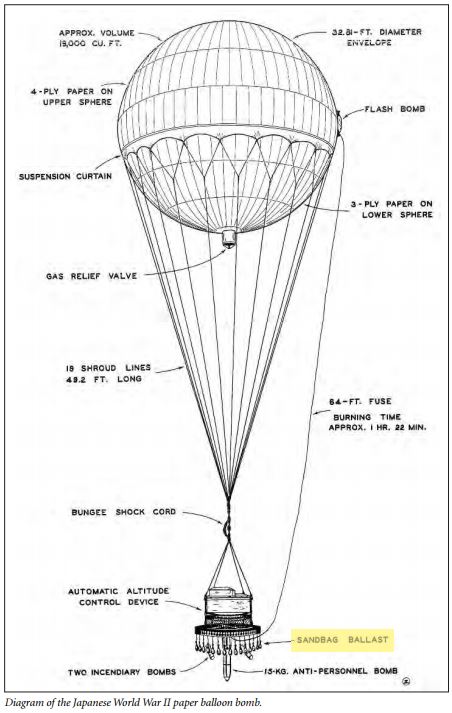

The ability to tie a sand, soil, sediment, or alluvial sample to a specific location is one of the most powerful tools of the science of forensic geology. Forensic geology is the study of the Earth and earth materials to solve crimes and aid in legal cases. The earliest and still the primary textbook on forensic geology was written by Rutgers University professors Ray Murray and John Tedrow in 1975. However, Professor Murray, and several others, credit Sir Arthur Conan Doyle as the originator of forensic geology. Doyle was the creator of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes in a series of crime stories that ran from 1886 to 1903. The character Sherlock Holmes claimed to be able to identify where an individual had been by various methods, including observing soil or clay on a person’s clothing or shoe and matching the material to a specific location based on his detailed study of the exposed geology of London. Forensic geology has been used by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other law enforcement agencies for many years to develop evidence and to match sediment samples to unique locations. Perhaps the most remarkable story of tying a sediment sample to a specific place occurred during World War II.  During World War II, the Japanese looked for a way to strike at the United States mainland. The Doolittle Raid in April 1942, launched in response to the the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, embarassed the military, and left the Japanese feeling vunerable. The American B-25 bombers struck Kobe, Nagoya, Yokosuka, Yokohama, and Tokyo. But after the loss of four critical aircraft carriers at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the Japanese no longer had any realistic chance of attacking the 48 contiguous states. This desire for relatiliation set in motion a Japanese balloon bomb project. During World War II, the Japanese looked for a way to strike at the United States mainland. The Doolittle Raid in April 1942, launched in response to the the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, embarassed the military, and left the Japanese feeling vunerable. The American B-25 bombers struck Kobe, Nagoya, Yokosuka, Yokohama, and Tokyo. But after the loss of four critical aircraft carriers at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the Japanese no longer had any realistic chance of attacking the 48 contiguous states. This desire for relatiliation set in motion a Japanese balloon bomb project.The balloon bombs were designed to carry high explosives and incendenary devices to the United States homeland. The incendary devices were intented to ignite woodland conflagrations. There was a widespread belief in Japan that the United States was a heavily-forested country where wildfires could cause major disruptions of the war effort and general panic. These were an early weapon of terror. The unmanned balloons were constructed of a laminated paper envelope 30 feet in diameter that held approximately 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen when fully inflated with a lifting power at sea level of one thousand pounds. The plan called for releasing armed balloons which would rise into the strong winds that flow during the winter months from west to east across the Pacific. A Japanese meteorologist had discovered these powerful winds at altitudes above 30,000 feet. This current of air later became known as the jet stream. The planners calculated that the armed balloons could cross the five thousand miles of ocean in three days. The Japanese had created the first intercontinental missile with twenty times the range of the German V-1 rocket. The technlogical problems for the developers were acute. In sunlight, the balloons would rise as the hydrogen heated and in darkness the balloons would descend. The repeated rising and falling would jeopardize the integrity of the laminated paper envelope and reduce the likelihood of a successful delivery. To address these issues, the planners added a release valve, altimeter, and ballast weights. The ballast would be automatically jetisoned as needed to maintain the optimum flight altitude. The ballast consisted of sand in a series of paper sacks mounted on the perimeter of the gondola. The sand for the ballast was collected from a beach nearby the site of the balloon launches. Between late 1944 and early 1945, the Japanese launched more that 9,300 balloon bombs at the United States. At least 300 of these weapons reached our shores. The bombs landed in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Michigan, Iowa, and Texas. Canada and Mexico also recorded arrivals of the balloon bombs.  Two balloon bombs landed in rural Texas. According the the Texas Almanac, one touched down in Desdemona in Eastland County and one in Woodson in Throckmorton County. Local reports indicate that, on March 23, 1945, local school children saw the Desdemona balloon drifting to the earth where they examined the device and collected pieces of it for souvenirs. Government officials arrived in Desdemona the next day to recover the wreckage and request the return of the “souvenirs.” Two balloon bombs landed in rural Texas. According the the Texas Almanac, one touched down in Desdemona in Eastland County and one in Woodson in Throckmorton County. Local reports indicate that, on March 23, 1945, local school children saw the Desdemona balloon drifting to the earth where they examined the device and collected pieces of it for souvenirs. Government officials arrived in Desdemona the next day to recover the wreckage and request the return of the “souvenirs.”Sixty miles to the northwest the following morning, Ivan Miller, a cowboy on the Barney Davis ranch eight miles north of Woodson, was checking cattle when he came upon a collapsed balloon. The balloon had a large rising sun painted on its top. The postmaster was notified soon after the discovery, and in the early afternoon, government officials arrived to take charge of the situation. As in Desdemona, school children showed great interest in discovery and took souvenirs. And again, government officials requested that the pieces be returned. At the time, it was inconceivable to American strategists that the balloons had travelled thousands miles across the ocean from Japan. Military leaders thought the balloons might be coming from West Coast beaches launched by landing parties. Other theories suggested the balloons were launched from submarines, nearby Pacific islands, German prisoner-of-war camps, or the Japanese-American internment centers. The United States government considered the balloon bombs a serious threat. They believed news of the waves of Japanese bombs drifting over the United States would spread a great concern through the American public. A strict news blackout was enforced to prevent the spread of reports of the airborne bombs and to keep the Japanese from knowing the effectiveness of the attacks. Many officials feared that the next step would be a balloon-borne bacteriological attack as Japan had previously lauched in Manchuria. Japanese propaganda broadcast s reported that great fires were sweeping though the forests of the western states and that the American population was in panic. Thousands of casualities were reported in the Japanese press. By early 1945, the American general public was becoming aware of the unusual threat. Despite the threat, the only American casualities of the balloon bombs were five Sunday school children and a minister’s wife. The minister and his wife had taken the children on a fishing trip in May 1945 to Bly in southern Oregon, east of the Cascade Mountains. They discovered a downed device which detonated and killed the six instantly. These were the only Americans killed in the continental United States by enemy action in World War II. Some of the bags of the sand ballast had been recovered from balloon crash sites. The sand samples were provided to the Military Geology Unit of the United States Geological Survey to see if they could determine the location where the sand was collected and thereby the launching site. The Military Geology Unit was established in June 1942, six months after the Pearl Harbor attack. The Unit studied battlefield locations to assist the armed forces with identifying building materials, drinking water sources, and suitable sites for the construction of airfields and other facilities. The Unit also studied beaches to develop recommended landing areas. The Unit had a wartime roster of 88 geologists, 11 soil scientists, 6 bibliographers, 5 engineers, 3 editors, 1 forester, and 43 administrative staff members. The Military Geology Unit was dissolved in 1975. To the geologists, it was immediately clear that the balloon ballast sand was not from North America or even from mid-Pacific islands. Using the tools available at the time, including polarizing microscopes and X-ray diffraction, the geoscientists delved into the genesis of the samples. Even with the small sample size, micropaleontogists were able to identify more than one hundred species of diatoms. Diatoms, a major group of algae, are abundant and widespread throughout the world’s oceans. There are three hundred genera of diatoms and twenty-five thousand species, and in one liter of sea water, there are one hundred thousand to one million diatoms. The ballast sand was obviously beach sand from a beach where there was a mixture of recent and fossil diatoms. Studying papers published by Japanese geologists before the war, the researchers were able to eliminate large parts of the county. Published papers described similar diatoms around Sendai, on the Honshu coast, northeast of Tokyo. Interestingly there was no trace of coral in the samples. Coral does not grow in cold water. In Japan, the northern extent of coral growth is near the latitude of Tokyo. The absence of coral fragments eliminated the beaches in the southern half of the country. Minerologists found an unusual suite of minerals that included no granitic material. This eliminated all beaches north of the thirty-fifth parallel where streams carry eroded granitic material from the inland areas. The mineralogists identified hypersthene, augite, hornblende, garnet, high-titanium magnetite, and hightemperature quartz. The high percentage of hypersthene and the unusal assemblage of minerals narrowed the potential locations of the balloon preparation area to just a few beaches. A foramiferia specialist on loan from Texaco looked at the sand samples for single-celled microscopic creatures with calcareous shells. The forams identified in the samples occurred on the east coast of Japan north of Tokyo and nowhere else on the planet. Finally, the Military Geology Unit narrowed the search for the balloon bombs origin to two locations roughly two hundred miles apart. Because of the absence of coral, geologists favored the more northerly location along the great beach of Shiogama, close to Sendai. Based on the geologist’s findings, aerial photo-reconnaissance was conducted identifying the balloon manufacturing facilties. American B-29 bombers destroyed two of the three hydrogen plants effectively ending the balloon bomb program. The war was largely over by the time the geologists’ work led the Army Air Corps to the balloon bomb hydrogen plants in 1945. So, while their efforts may not have had any direct affect on the ultimate outcome of the conflict, the geoscience community stepped up aid in the United States in a time of national threat. |

source:

Michael Forlenza, P.G.

releasedate:

Friday, November 1, 2013

category:

Articles

subcategory:

From the Editor

Forensic Geology: Paper Balloons and Sand

Forensic Geology: Paper Balloons and Sand